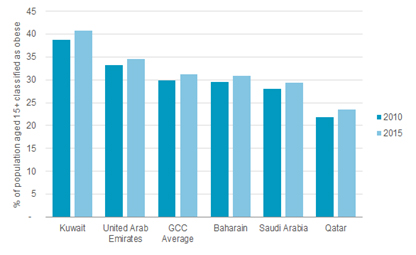

Regular physical activity brings multiple health-related benefits. However, it seems that sufficient physical activity levels are still far from being achieved at a population level. We can define physical inactivity as an activity level insufficient to meet the current physical activity recommendations.1 Based on the global physical inactivity research published in Lancet, inactivity levels exceed over 70% in some countries.2 For example, in Middle East countries, physically inactive are around 35 %.2 In addition to this, inactivity also goes hand in hand with overeating. Results from research in Dubai implicates that almost 85% of evaluated subjects had 1 or more risk for developing cardiovascular diseases.3 In addition, a school-based study revealed that around 30.5% of male children were overweight or obese.4 The community has to be concerned knowing these numbers and with the not-optimistic prediction for the future. If we don’t change something globally at the community level, we will probably continue to report these or even worse numbers. In the future, people in GCC must take action at the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and community levels. This article will explain one of the main reasons for the current situation and present one good example of government intervention and community engagement in a mission to improve health and quality of life among their cities.

How did we end up in this situation?

To better understand modern problems, it would be helpful to understand and know our past. From the early beginnings, people lived in small groups or “packs”; they were nomads and hunters. They collected food in nature and had a very diverse diet. They moved around a lot, and they were often hungry. Later, they realized that they could control some agricultural crops and began to tame animals. After that, they started living in settlements, the number of people increased. Fast forward to 2000 years ago, the human race numbered around 200 million people.5 We reached the first billion in 1800. Nowadays, the world is approaching the number of eight billion people. We developed very quickly, but our physiology did not follow our progress. Notably, we live longer than before, thanks to better healthcare systems, medication, and an overall higher quality of life.6 However, modern value systems have weakened our overall resilience.7 As a result, people are more stressed and burnout, and overall more anxious.8 All of this comes with our unhealthy lifestyles. For example, imagine regular Joe and one day in his life. He wakes up in the morning and goes to work by car. He is an accountant and sits 80% of his work time. After long 8 hours of work, he is finally home, ready to watch his favorite tv show. Nevertheless, Joe likes fast food. Day after day, these routines are repeated, and our Joe is now obese, with one or several factors of cardiovascular or metabolic diseases. The hypothetical story of Joe may be exaggerated, but we, like beings from a physiological point of view, are not accustomed to a sedentary lifestyle.The number of obese has exceeded the number of malnourished, and worldwide, more people die as a result of obesity than hunger.10 Obesity is a problem of the modern age. It should be studied from a psychological, sociological, and physiological point of view.

Around 80-90% of health outcomes are a consequence of external and environmental factors.7 Therefore, we cannot stay happy and healthy without creating environments that support our wellness rather than reducing it. Education about physical activity and nutrition and encouragement of the people through community and government interventions is the key in a mission to tackle obesity and improve health and overall quality of life. Knowledge is the key to any change.

Copenhagen as an example

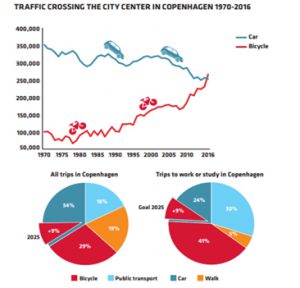

Today we want to highlight one good story. How the government and community intervention can change healthcare. It is a story about Copenhagen, a city of cyclists.11 Although we are not living in Denmark, this story can serve as an example to change something in our environment and encourage people to participate in more physical activity. Cities have been created for cars and drivers. This, of course, has brought the economy up and produced several advantages. However, nowadays, the vehicle that was supposed to give freedom in mobility are stuck in traffic. As a result, they are one of the most significant air pollutants contributing to climate change. Copenhagen is the city of cyclists. But for this phenomenon, they didn’t give credit to the unique cycling gene or because they care about the environment more than other people all over the world. They are cyclists because Copenhagen is built for cyclists. During the half of the 20th century, Copenhageners demonstrated in the streets, demanding that cycling should be prioritized over cars.12

Copenhagen in numbers https://international.kk.dk/sites/international.kk.dk/files/velo-city_handout.pdf

Subsequently, authorities, politicians, and planners listened and started to design a new city more suitable for cycling. The city’s investment in majestic cycling infrastructure is paying off in many ways. Besides numerous health benefits, there are some serious economic benefits too. Today, around 50% of all trips to work and education in Copenhagen are made by bike. The number of bicycles has exceeded the number of cars. It’s safe, fast, and fun. For example, using cycle, you can come faster to your work. Some companies also provide a bonus for the active transport of employees. Also, the health outcome of these behaviors results in fewer cardiopulmonary diseases, cancers, strokes, and type 2 diabetes.12 In the end, did you know that people in Denmark are the happiest people in the world?13 Think about the reasons.

It is inspiring to know is the GCC governments, lead by the KSA and UAE, have taken serious action to increase the sports participation rate, and such initiatives will be further discussed in our upcoming blogs.

About DUDI

DUDI is an all-sports social marketplace. Our mission is to empower sports communities and we aim to increase sports participation rate in the GCC region through community engagement and technology.

– copyrighted by DUDI Sports Technologies FZE

Reference

- Lee, I. M., Shiroma, E. J., Lobelo, F., Puska, P., Blair, S. N., Katzmarzyk, P. T., & Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. (2012). Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The lancet, 380(9838), 219-229.

- Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2018). Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1· 9 million participants. The lancet global health, 6(10), e1077-e1086.

- Yusufali, A., Bazargani, N., Muhammed, K., Gabroun, A., AlMazrooei, A., Agrawal, A., … & Alsheikh-Ali, A. (2015). Opportunistic screening for CVD risk factors: the Dubai shopping for cardiovascular risk study (DISCOVERY). Global heart, 10(4), 265-272.

- Hussain, H. Y., Al Attar, F., Makhlouf, M., Ahmed, A., Jaffar, M., Dafalla, E., … & Wasfy, A. (2015). A Study of Overweight and Obesity amon g Secondary School Students in Dubai: Prevalence and Associate d Factors. International Journal of Preventive Medicine Researc h, 1(3), 153-60.

- https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/world-population-by-year/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC. (2003). Trends in aging–United States and worldwide. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 52(6), 101-106.

- https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/resetting-the-world-with-wellness/

- Rappaport, S. M., & Smith, M. T. (2010). Environment and disease risks. science, 330(6003), 460-461.

- https://www.euromonitor.com/article/rising-obesity-rates-gulf-states-create-opportunity-health-positioned-beverages

- Abarca-Gómez, L., Abdeen, Z. A., Hamid, Z. A., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M., Acosta-Cazares, B., Acuin, C., … & Cho, Y. (2017). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128· 9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The lancet, 390(10113), 2627-2642.

- Pucher, J., & Buehler, R. (2008). Making cycling irresistible: lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transport reviews, 28(4), 495-528.

- https://eu.boell.org/en/cycling-copenhagen-the-making-of-a-bike-friendly-city

- Holm, A. L., Glümer, C., & Diderichsen, F. (2012). Health Impact Assessment of increased cycling to place of work or education in Copenhagen. BMJ open, 2(4), e001135.

- Biswas-Diener, R., Vittersø, J., & Diener, E. (2010). The Danish effect: Beginning to explain high well-being in Denmark. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 229-246.

- https://international.kk.dk/sites/international.kk.dk/files/velo-city_handout.pdf